The European Commission has published the text of its provisional decision last September to block the proposed €1.63bn acquisition by Booking (the leading hotel online travel agency (OTA) in Europe) of eTraveli (one of the main flight OTAs in Europe).

Although it marks only the EC’s eleventh prohibition vs. around 3,500 approvals in the last decade, the decision has made headlines as a notable example of EU/UK divergence, with the UK CMA clearing the deal unconditionally at phase 1. It also represents a clear departure from established EC merger guidelines and introduces a novel “ecosystem entrenchment” theory of harm in a relatively mature market (travel), without obvious guardrails.

Booking is appealing the decision before the EU Courts and all eyes will be on the outcome. In the meantime, we give our take in this post on some of the EC’s key reasoning and consider the practical implications for future M&A in the tech sector and beyond.

Summary of the EC’s concerns

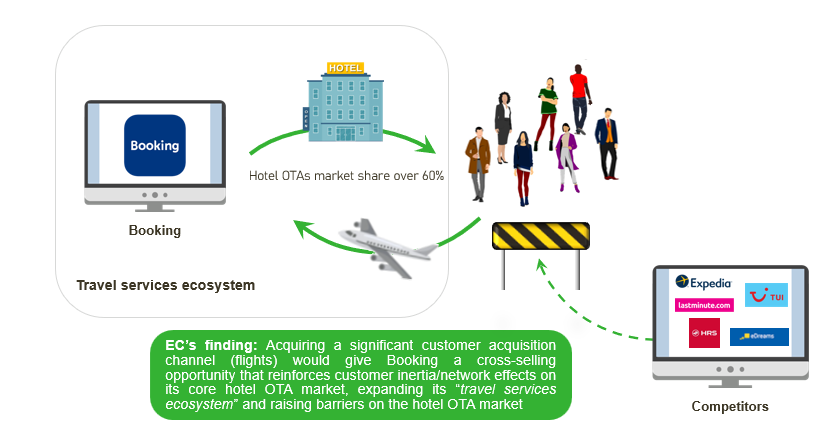

The EC’s concern centered around how acquiring eTraveli’s flight booking service would strengthen Booking’s existing dominant position (~60% market share) in the hotel OTA space: “Booking would leverage its ability to acquire customers in the neighbouring flight OTA market to strengthen its dominant position in the hotel OTA market“. Specifically the EC found that:

- The main rationale of the deal (even if not the only one) was to enable Booking to increase its sales in the hotel OTA market.

- The deal would allow Booking to acquire a main customer acquisition channel (flight booking services), thereby expanding “its travel services ecosystem” which revolves around its hotel OTA business, by allowing Booking to offer customers the “Connected Trip“, whereby customers are driven to attach hotel reservations to their flight purchases.

- Given customer inertia (customers tend to make purchases on the same site rather than shopping around), customers would likely stay on Booking’s platform to shop for other services, which would make it more difficult for other hotel OTAs to compete and potentially lead to higher costs for both hotels and consumers.

- By increasing traffic to – and sales by – Booking’s platforms, the deal would have reinforced network effects and increased barriers to entry or expansion, making it harder for competing OTAs to develop a customer base capable of supporting a hotel OTA business.

Booking offered a behavioral remedy whereby flight customers would be presented with a “choice screen” on the flight check-out page, allowing them to select rival hotel offers (ordered by price by Booking’s KAYAK algorithm). The EC rejected this remedy as insufficiently transparent/non-discriminatory and too difficult to monitor (KAYAK was described as a “black box”).

Main observations on the EC’s “entrenchment” theory

This case is often defined as one of the latest examples of the (arguably) novel “ecosystems” theory of harm being deployed by antitrust agencies. But the decision, whilst explicitly referencing Booking’s travel services ecosystem, burns its calories on an entrenchment of dominance theory, based on a nominal market share increment.

Across the 300-page decision, there are several notable elements worth drawing out, with important practical implications for future deals:

- Market shares: how low can you go? The minimal increase in market share (1-5%) required to entrench Booking’s dominant position is striking compared with established filters for competitive harm. The EC essentially says that any increase would further entrench Booking’s dominant position, so even one additional customer post-merger would be too many. This sets an exceptionally low threshold for showing effects, with no clear limiting principle.

- Customer inertia as a barrier to entry. The barrier to entry in this case allegedly lies in the customer inertia, meaning many customers using eTraveli as their flight OTA would end up staying on the Booking platform if they are cross-sold for their hotel OTA purchase. So the fundamental question is whether or not customers are one-stop-shoppers or mix-and-matchers. But what if “customer inertia” is actually a sign of customer benefit/value? Indeed, the decision itself quotes Booking CEO Glenn Fogel: “They go to one player because they know that’s the place where they’re going to get the most value.”

- Is there still such a thing as a non-horizontal merger? While the parties argued they were separate but complementary businesses, the EC characterized the transaction as having both elements of a horizontal and non-horizontal merger (despite no overlaps): “it would likely involve effects on the hotel OTA market that would typically result from a horizontal merger in that Booking may further entrench its position on that market. However, these effects arise since the transaction would enable Booking to acquire a target present on an upstream market which constitutes an important acquisition channel.” Does this signal a move away from classifying mergers as non-horizontal even when there are no horizontal overlaps? And what does that mean for how agencies (and parties) should assess them?

- Discarding the Non-Horizontal Guidelines for dominant acquirers. It is well established that merger notices and guidelines play an important role for the interpretation of the EU Merger Regulation. However, the decision states that: “In the face of dynamic and rapidly changing economic reality, the Non-Horizontal Guidelines cannot relieve the Commission, in circumstances that were not envisaged by them, from its duty to examine whether a concentration may significantly impede competition in the internal market or in a substantial part of it, in particular as a result of the creation and strengthening of a dominant position.” So even for the non-horizontal effects of the deal, the EC departed from the legal clarity of the 2008 Non-Horizontal Guidelines on the basis of the intervening evolving economic reality. Perhaps this signals an upcoming update to the Guidelines. In the meantime, what is the framework for assessment that merging parties can rely on? And what (if not the Guidelines) are the limiting principles to the EC’s discretion when applying that framework?

- What is the appropriate counterfactual? The parties argued that the appropriate counterfactual to assess the effects of the deal was the current commercial partnership arrangements between them (currently the “phase 2 agreement”), through which eTraveli provides flight OTA content to Booking in exchange for a fee, which Booking then sells through Booking.com. The EC rejected this, largely on the basis that the phase 2 agreement was negotiated in parallel with the transaction as a “natural experiment”, and the parties would be likely to terminate it absent the transaction. Meanwhile, following the decision, Booking announced an extension to the phase 2 agreement through at least December 2028.

- Central role of internal documents – and not just the “hot” ones. The EC relied heavily on internal documents as is shown throughout the decision, including around the deal rationale and the nature of the deal vs. the phase 2 agreement (see above). This is in line with a growing trend of giving particular weight to internal documents, or to a subset of them, while rejecting others. Internal documents are important to ground the legal and economic assessment in facts, but it is also important to give the appropriate weight to different types of evidence – especially when evidence is unclear and open to different interpretations. This case highlights the need for caution when business teams and/or third party advisors produce deal-related and other internal documents (especially to “sell” a deal), which could be misinterpreted by agencies later on.

What next for “entrenchment”: Looking to the US and UK

The EC’s entrenchment theory of harm has clear parallels with the US approach, as set out in the new joint FTC/DOJ merger guidelines. The guidelines include a new and keen focus on scrutinizing mergers that entrench the position of an already dominant firm, or extend a dominant position into new markets. As part of the assessment, the agencies will consider the merger’s impact on fixed factors like product quality, and may also look at the (often longer term) impact on market power and industry dynamics. The guidelines reflect recent practice. For example, the FTC invoked an entrenchment theory in Amgen/Horizon Therapeutics (which resulted in a rare behavioral settlement). It also featured in more recent FTC/DOJ cases such as Tapestry/Capri and UnitedHealth/Amedisys, and we can expect it to be a clear enforcement focus going forward.

We can also expect to see more thinking from the UK CMA on the meaning of “entrenchment”. Having “substantial and entrenched market power” in relation to a digital activity is a key element for establishing strategic market status under the new DMCC Act (see our previous post). The CMA has confirmed in its draft digital guidance that these concepts are legally distinct from dominance, but without (yet) providing a clear alternative framework for assessment.