The long-awaited Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Bill has received Royal Assent and became UK law. As discussed previously, this is the final legislative step to implement a significantly bolstered competition and consumer regime, as well as a brand new digital regime, all administered by the Competition and Markets Authority.

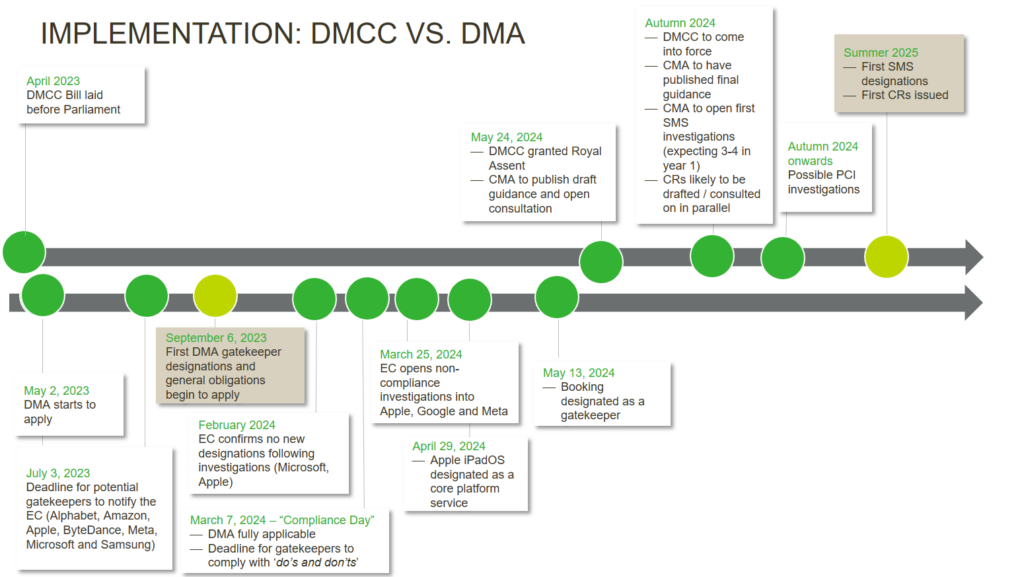

The DMCC follows on the heels of the EU’s own answer to digital regulation – the Digital Markets Act – already in force since May 2023, with initial rounds of gatekeeper designations and the road to compliance well underway.

Businesses will need to get to grips with the significant changes brought about by the DMCC and consider their practical impact, as well as their interplay with their DMA counterparts. As businesses continue on their journey to regulatory compliance, what can we expect next in terms of key milestones and how can businesses help to shape the DMCC’s application and enforcement?

Countdown to the new digital regime

Operating in shadow form since April 2021, the CMA’s Digital Markets Unit will finally gain its new statutory powers to regulate the largest tech firms, turning the CMA from its 10-year role as an authority into a regulator. The CMA is consulting on draft guidance on how it will apply its new powers in practice, as well as continuing its outreach to stakeholders, including via roundtables. It will publish the final guidance ahead of the regime’s entry into force – still expected to be in Autumn 2024. We will be responding to the consultation, which closes on 12 July 2024, and would be happy to discuss our response with you.

The digital regime has five core elements which the DMU will have broad discretion (tempered by relatively limited judicial oversight) to administer, and it intends to hit the ground running:

- SMS designations. One of the DMU’s first tasks will be to designate relevant tech firms as having “strategic market status” in relation to specified digital activities. The CMA expects to launch its first SMS investigations shortly after the DMCC enters into force, with 3-4 SMS investigations in the first year (and 1-2 open at any one time given resource limitations). The designation process is likely to last up to 9 months (vs. 18 months for “traditional” market investigation references), meaning the first designations won’t happen until at least Summer 2025. The CMA currently has 11 digital activities in mind, and has indicated that it will prioritise digital advertising.

- Conduct requirements (CRs). Alongside the SMS investigations, the DMU will consult on the tailored, firm-specific CRs it will impose (subject to a proportionality test) for each SMS firm, aiming to publish them at the same time as the SMS designations. Given that CRs are firm-specific, they are likely to vary substantially – unlike the more prescriptive do’s and don’ts under the DMA.

- Pro-competitive interventions. The DMU also aims to begin its first PCI investigations shortly after commencing the draft CRs and expects this work to be ongoing throughout Summer 2025. PCIs allow the CMA to target digital activities which are seen as harming competition, and could be behavioural in nature, or entail the structural/operational separation of the firm’s business units.

- Mandatory merger reporting. In a big shift from the UK’s (technically) voluntary/non-suspensory merger regime, SMS firms will need to report M&A deals prior to closing when (1) they acquire shares/voting rights exceeding thresholds of 15%, 25%, or 50% in a target with a UK nexus; and (2) the deal value exceeds £25m. This reporting obligation is potentially much broader than its DMA equivalent, since it relates to any mergers meeting the relevant thresholds, regardless of whether the target is active in digital services or the collection of data. The CMA’s ability to review deals reported under the DMCC may also be much greater than the EC’s equivalent ability under the DMA, depending on the outcome of the pending Illumina/Grail appeal. Should the EU Court of Justice follow Emiliou AG’s opinion and reject the EC’s expansive interpretation of Article 22 EUMR, reporting mergers under the DMA will not mean that they can actually be reviewed unless they meet relevant EU/national merger thresholds – in which case they would need to be notified in any event.

- Enforcement powers. The CMA will be able to impose significant sanctions, including fines of up to 10% of global revenues and individual director disqualifications for breaches of CRs or PCI orders.

Enforcement timeline: DCMCC vs DMA

Countdown to bolstered powers for competition enforcement

Likely from Autumn 2024, the DMCC will also confer on the CMA significantly greater competition powers, aimed at boosting its enforcement capabilities as well as increasing deterrence. For example, the DMCC:

- Extends the prohibition of anti-competitive agreements to conduct which happens outside the UK as long as it is likely to have an “immediate, substantial and foreseeable effect” on trade within the UK;

- Strengthens the CMA’s information and evidence gathering powers, including by applying them outside the UK and enabling the CMA to seize and sift evidence from domestic premises, which is seen as increasingly important in a remote-working world; and

- Increases the current merger control turnover threshold modestly from £70m to £100m and – more critically – introduces a new so-called “acquirer threshold” which allows the CMA to review no-increment deals where (1) one party has at least 33% UK share of supply and a UK turnover above £350m, and (2) the target business has a UK nexus. While the UK regime will remain voluntary and non-suspensory in principle, more merging parties will need to consider its potential impact at the outset of their deal and in light of the CMA’s enforcement priorities.

Countdown to comparable consumer enforcement powers

The DMCC also grants new protections for consumers designed to ensure they are making informed and reasoned decisions, coupled with direct enforcement powers for the CMA on a par with its competition arsenal. The CMA will be empowered to decide, without court proceedings, whether a consumer law has been broken and to issue fines (up to the higher of 10% of global turnover or £300,000). The CMA will look to cut down the traditionally lengthy enforcement periods, having found it took on average 20 months to bring successful claims under the previous regime.

Based on its stated priorities, and in the face of ongoing cost of living challenges, the CMA is likely to focus initially on at least two core areas:

- essential spending, particularly where choice architecture or misleading pricing can play a role, e.g. by enforcing against harmful online selling practices, hidden/drip fees and fake reviews, as well as subscription traps; and

- broadening its green claims work (having already opened investigations into greenwashing in fashion and FMCG), and bolstering competition in green innovation markets.

Along with the new digital regime, most of the new powers are expected to come into force in Autumn 2024, with others (e.g. those relating to subscription traps) following in 2025 at the earliest.

New rules for media mergers with immediate effect

The DMCC gives the UK government new powers to intervene in transactions involving foreign state ownership of UK newspapers and periodic news magazines. The UK government launched a consultation (which has been extended to July 9, 2024) on draft regulations to create targeted exemptions for specific types of passive investment up to a low threshold.

Unlike the rest of the DMCC’s provisions, the new rules apply immediately on Royal Assent (i.e. from May 24, 2024). Whilst in reality they will only capture a small cohort of mergers, it is important to be aware of them when contemplating acquisitions – even of very small interests – in the media space.

This move is in line with a wider global trend of expanding the notion of what and who governments perceive as threats to national security, and using new (rather than existing) legislative tools to scrutinise investments and intervene, for example in relation to ongoing attempts in the US to ban TikTok. We will be delving deeper into these issues and their impact on dealmaking in a future post.